Why smart-city tech has lost its buzz

Smart city projects haven’t panned out how originally envisioned because of COVID-19.

Just a few years ago, smart cities, a catch-all phrase for connecting urban infrastructure like parking meters and stoplights online, had major buzz. The idea was to use machine learning to crunch data collected across cities to, for example, minimize traffic delays and reduce pollution.

But smart city projects haven’t taken off as quickly as expected, partly because of COVID-19 decimating local economies and reducing city budgets.

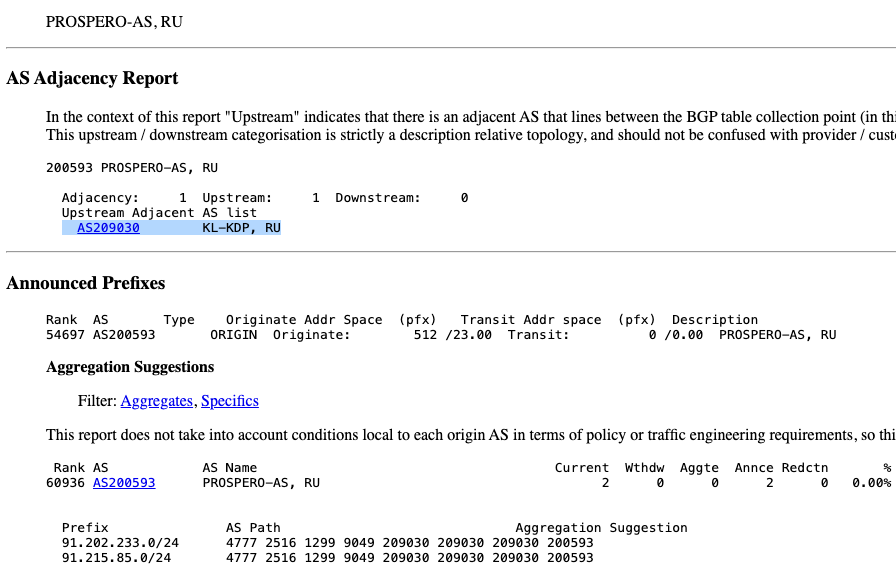

One of the latest smart-city causalities was Cisco’s ambitious Kinetic for Cities software, a dashboard for governments to manage data from their local smart-city projects. Cisco said in December that it would kill the product.

“The cities realized that that’s not what they actually need,” said Cisco global innovation officer Guy Diedrich.

Instead of pushing its software, Cisco plans to work with city governments on other efforts involving Internet connectivity. The company recently worked a lot with local officials to install basic Internet infrastructure, for instance, like helping Brazilian cities create virtual courtrooms, he said.

Forrester analyst and smart city expert Michele Pelino said local governments are feeling pressure to keep city operations humming despite shrinking budgets. Because smart city projects can be expensive and often don’t pay off for years, they’re being cut back.

Furthermore, some smart city projects had been focused on fixing problems that are no longer as pressing. Reducing traffic and parking now in many cities isn’t as important because many workers no longer commute to downtowns because of shelter-in-place rules.

Now, city governments see “security and safety” as a priority, and have reallocated some of their budgets to solve the problem, Pelino said.

“People need to feel comfortable that they are coming into an environment that is safe and secure,” she said about these kinds of projects.

Pelino is unsure when more ambitious projects, like using machine learning to optimize traffic lights, will be reinstated. She’s “certain” that bigger projects will eventually come back, but for now, many cities don’t have the money.

“Where is the money going to come from?” Pelino said.

As for Cisco, shuttering its smart city technology is another example of its challenges in expanding beyond its core networking gear business. Although the networking giant has been pushing into new areas like selling more specialized chips and networking software, the company’s overall business is still shrinking as firms buy less routers and switches than they used to, partly due to the rise of cloud computing.

Diedrich is still optimistic about Cisco’s smart-city push, saying that the company must still learn about it by working with governments via its Country Digital Acceleration (CDA) program, intended to help various governments with their digitization projects.

“What we learned with coming to cities, is that their needs are evolving and changing in real time,” Diedrich said. “One thing that we’re not doing is coming up with what we think cities need and shoving it down their throats—that’s not Cisco and certainly not the CDA program.”

As to whether Cisco would have kept selling its Kinetic for Cities software if it wasn’t for the coronavirus pandemic, Diedrich was vague. One thing that is certain: any smart city projects the company pursues will involve artificial intelligence.

Among the local governments still testing smart city projects, officials “know A.I. and machine learning is going to be very important,” said Diedrich, adding that it’s needed for making quick decisions like adjusting traffic lights quickly.

Jonathan Vanian

@JonathanVanian

jonathan.vanian@fortune.com